STAR JUNCTION, PA

This was the "manway" for the Washington No. 2 mine at Star Junction, PA, opened by the Washington Coal

and Coke Company in 1893. A few of the coke ovens are still there as well. Once Star Junction contained over 1000 beehive coke ovens, which probably tied it with

Standard in Westmoreland County for the largest coke yard in the nation.

These company duplex houses in the "Turkey Knob" section of Star Junction were built in the 1910s.

However, these patch houses were constructed by Washington Coal and Coke Company in the 1890s.

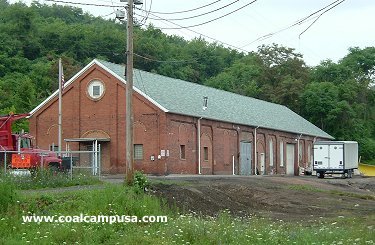

The power house still stands at Star Junction. IN 1930 H.C. Frick Coke, a subsidiary of U.S. Steel purchased the Star

Junction coal mines, coke works, and patch town. This was the last coal property purchased by U.S. Steel.

The HABS/HAER survey took this photo in the Star Junction patch in 1988.

Ruins of beehive coke ovens at Star Junction.

Suzanne writes, " I [was] looking for information & photographs about coal mining

in

the Perryopolis-Star Junction (Fayette County) area. My grandfather,

John Bubnash, mined in that area for many years. He came to the US

from

Zemplen Co. in the old Austro-Hungarian Empire, in 1910. He started

out

in Webster, then Snowden (Clairton area), Monessen, Donora, Star

Junction, Perryopolis, Rowes Run. He worked until Feb. 1951, when he

was

involved in a slate fall at Colonial #3 at Rowes Run. He was partially

paralyzed in that accident, and my Baba took care of him full-time the

next 15 years, until his death in 1966. His older brother had been

killed in a slate fall in Stockett, Montana, in 1909. While

interviewing

my Baba one time, she expressed her opinion of coal mining (in her

Slovak

version of English) as follows, 'I told my boys, even if you have just a cup

of

coffee a day, don't go in mine never!' And none of her sons became

miners.

Suzanne also quotes her father talking about life at Star Junction:

"'We moved into a house in the Red Row area of Star Junction, about two miles from Perryopolis, in October 1929, when I was eight years old. It faced west toward the highway. This house had about the most sub-standard living conditions that you can imagine. It was a block house with maybe four or six families, like a present-day condominium. Each apartment (we called it a house) had only two bedrooms, a kitchen, and a small living room. It was very, very bare. One of the sleeping areas had no window. We did have electric lights and running water, but very poor water—a lot of sulfur in it and hardly drinkable, but we had to drink it. The electric lights were direct current (DC). As the generators produced the electricity they didn’t always run at the same speed, so the lights would get brighter and dimmer, then brighter and dimmer. The bulbs were the clear kind where you could see the filament. I guess the coal company manufactured the electricity, and nobody ever turned the lights out, because it

didn’t seem to matter whether they were on or off, because electricity kept coming through. The Yonok family moved into this place the same time we did, and when they tore out the fireplace cockroaches ran everywhere.

This house was right next to the mine entry. There were coke ovens all over the place. In fact, the coke ovens across what is now Route 51 put out so much light, that a newspaper could be read at night in Red Row. After the clinker coke was taken out of the ovens and put into the railroad cars, there were a lot of ashes left over, which were dumped wherever there was room. The houses where we lived were built after they coal company had spread the cinders. Grass wouldn’t grow because there was no dirt, only cinders. When the wind blew, the cinders flew around—it was terrible. We only lived there for about a year and then moved to a better house.

The other house was a two-family house a half mile away, also in Star Junction, in an area called New Town. It had a nice green lawn and a big garden in the back. The lots were something like 60 x 200 feet, a fairly good size. We had no inside plumbing—none of the houses did where we lived up to that point. Once or twice a year the outhouses had to be cleaned out. Men came with tank trucks and they actually emptied the hole in the ground with buckets on long poles. It was an exciting thing, and the guys who cleaned the outhouses were called 'honey-dippers.' We always looked forward to the honey-dippers coming. They did their work at night and would really smell up the neighborhood. There was a place on the west side of 51 on the way to Star Junction (past the Dairy Queen) called 'Sweetcake and Victoria.' That’s where the honey dippers dumped their loads.

Miners were not paid much in those days and it was not unusual for them to strike for more wages and better working conditions. In the early 30’s, maybe about 1933, there was a widespread serious strike and the State Militia was called into Star Junction to maintain order. Most of the trouble was centered in the middle of town where the company store and doctor’s office were located. The militia used machine guns and tear gas to control the crowd of several thousand strikers who came from other areas. I think they were just milling around and not being destructive. John was subjected to tear gas once, and picketers were injured by the guns fired into the crowd. At that time I had scarlet fever and could not leave the house to observe the action. One day I looked out the window and saw about 27 company security men escorting four miners into the mine to work. Father owned a .38 pistol which he kept in a shiny cardboard box. During the strike he went to town with his pistol even though Mum pleaded with him not to take it. As far as I remember this was the only time he went to the picket line. He was unemployed at the time of this strike.

My Father was out of work much of the 1930’s and I don’t know how we survived. From about 1937 on he had a steady job and I remember he would bring home about $55 for two weeks work—that was a big deal. Many miners were injured in the mines, including my Father, who suffered a broken back and other injuries when he was 60. Black lung disease (from breathing coal dust) was prevalent and many miners died from it.'"

Image courtesy Coal and Coke Heritage Center, Penn State Fayette

2004 image by author

2004 image by author

2004 image by author

Historic American Engineering Record image

2018 image by author